Pheng Kea, Executive Director, RWC

Abstract

Around the world, 663 million people still lack access to improved drinking water sources. Water is fundamental for human life and thus access to clean water is a basic human right. At the very least, one should have daily access to a minimum of 20 litres of clean water for basic needs.. Both the quality and quantity of water supply must be ensured to meet people’s basic needs for drinking and cooking.

Cambodia Sustainable Development Goals #06 aims to increase national access to improved water supply to 100% by 2025. In 2016, 61% of Cambodians had access to improved water supply of which 53% lived in rural areas. In order to achieve the goal, the Cambodian Ministry of Rural Development (MRD) has established the National Action Plan (NAP) to be implemented testosterone cypionate 250 mg for sale

from national to sub-national levels. Under the NAP, the MRD and WASH sector have jointly developed either a provincial action plan or a district action plan for a more specific implementation in these areas.

Rainwater is in abundance in Cambodia: there is enough annual rainfall to cover both domestic water supply and irrigation needs. But for rainwater systems to be considered an improved source, the water must be stored in a single tank with a capacity buy of at least 3,000 litres. It also requires certain types of roofing and storage to ensure the water is clean enough to drink at all times. Rainwater systems are ideal for Cambodia, where many people already have the right types of roofing installed. However, current systems are too small to store water for the dry season and do not store the water in a safe manner.

This article combines a literature review, experience and the findings of studies undertaken by RainWater Cambodia (RWC). The first step is to understand the government’s effort to implement the national action plan on water supply. The second step is to examine the community’s perception on traditional rainwater harvesting in rural Cambodia, and the third step is to investigate the sustainability of using risk-managed rainwater harvesting systems promoted by RWC in terms of physical condition, ability to maintain and user perceptions in rural Cambodia with the objective of improving access to water and make drinking water affordable, convinience and realizable in Cambodia..

Key words: roof harvesting, rainwater, formalization and rural Cambodia

generic cialis pills gaining symptoms and losing 1. Introduction

1.1 Global water supply situation

Around the world, 663 million people still lack access to improved drinking water sources (JMP update report 2015, p4). Water is fundamental for human life, and thus access to clean water is a basic human right. At the very least, one should have daily access to a minimum of 20 litres of clean water for basic needs (Kevin Watkins, 2006). Water supply refers to large utilities with piped distribution systems, piped and non-piped community supplies including hand pumps, and individual domestic supplies (WHO 2005). Both the quality and quantity of water supply must be ensured to meet people’s basic needs for drinking and cooking. Significant disparities exist between urban and rural access to improved water supplies. Around the world, improved water supplies are available to 96% of urban communities and to 84% of rural communities (JMP update report 2015, p54).

1.2 Cambodian SDG 06 and water supply in Cambodia

In the Cambodian context for Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), the Cambodian government sets for the country some ambitious access to water objectives: “Universal access to improved water by 2025” and “Universal access to safe water by 2030” (SEVEA 2017).

Cambodia has many alternative water resources such as Tonle Sap Great Lake, the Mekong River, and groundwater. According to data collected from the Cambodia Socio-Economic Survey, the number of households with access to improved drinking water source is 61%, of which 53% are in rural areas (CSES 2016, p13). To monitor the progress of SDGs and the National Strategic Development Plan (NSDP) 2014-2018, the Cambodia Socio Economic Survey (CSES) results are collected and used for updating the progress.

Access to an improved water supply is defined as “the availability of an improved water source within 150 metres of a house,” and an “improved” water source is one that is more likely to provide “safe” water, such as direct piped connection to the house or a borehole, (NAP, 2014). Rainwater collection is also considered as an improved water source if the rainwater catchment tank is completely closed, has a tap to withdraw water and has a capacity of at least 3,000 liters (CSES 2016, p13).

1.3 Rural water supply informed choices in Cambodia

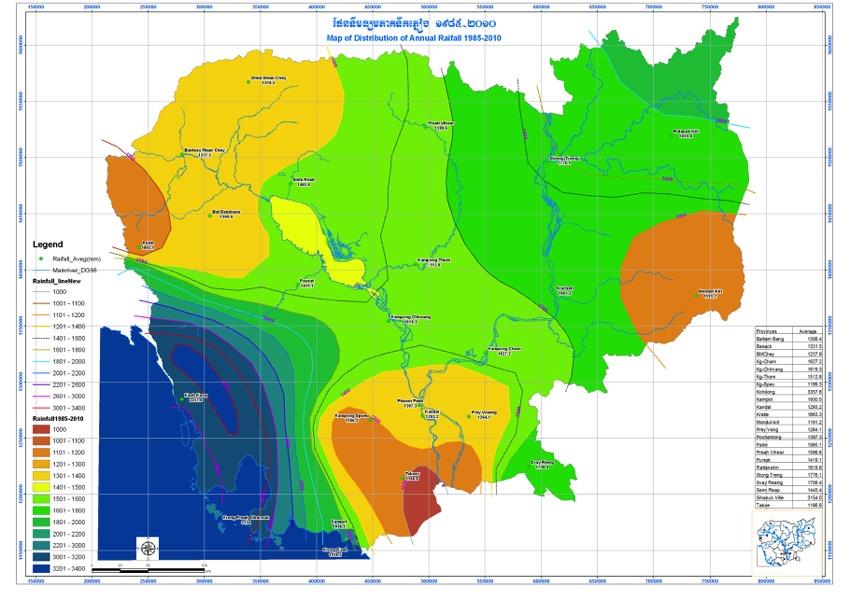

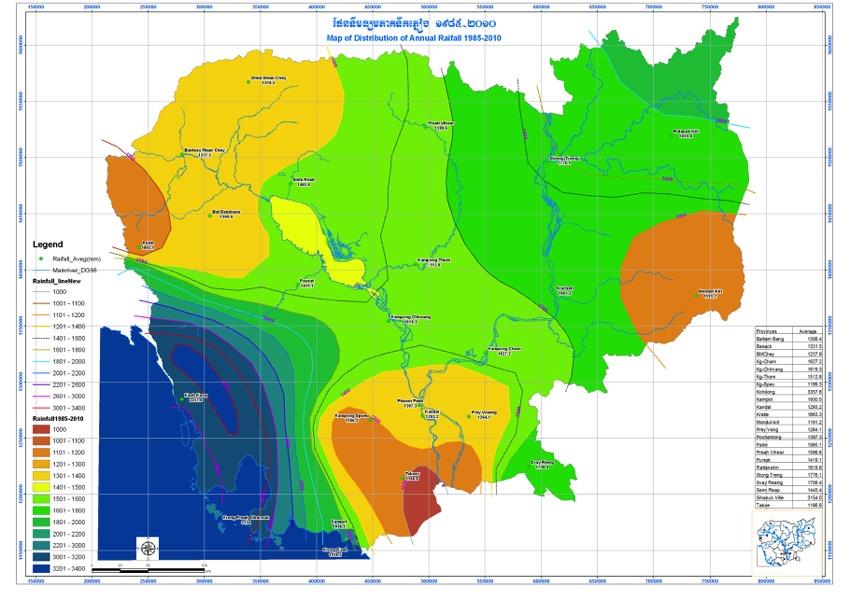

Cambodia is considered one of the most water-abundant countries in the region, and there are two main types of water available in Cambodia: approximately 75,000 million m3 of annual surface water runoff and 17,600 million m3 of groundwater in aquifers. Precipitation varies from 1,400 mm to 3,500 mm annually, depending on the areas and number of rainstorms (Kyoochul Ha 2013, P.36).

The selection of the appropriate type of water supply is hence a fundamental step to ensure the reliable access to high-quantity water. There are a number of water sources, which rural areas can rely on: rainwater (different designs of tanks and jars), surface water (reservoirs, rivers, streams and others) and groundwater (dug wells and boreholes). However, each water source provides water with different quantity and quality depending on its nature (SNV-MRD 2015, p.23).

1.3.1 Surface water

Surface water appears either as direct runoff flowing over impermeable statured surfaces that is then collected in large reservoirs and streams or as water flowing to the ground from surface openings. Generally, surface water is water found in lakes, streams and rivers. In Cambodia, all sources of surface water are categorized as unimproved water sources and not recommended as source for rural water supply, unless treatment is incorporated (SNV-MRD 2015).

1.3.2 Groundwater uses

Groundwater is the water located beneath the earth’s surface in porous soil spaces and in the fractures of rock formations. Shallow groundwater is generally extracted through dug wells, while deep groundwater is extracted from boreholes. Moreover, groundwater is considered as an improved source for water supply (SNV-MRD 2015, p.24). Groundwater is suitable for irrigation use, but high levels of arsenic, iron, manganese, fluoride and salt are observed in some areas; and 53% of Cambodian households drink

from groundwater sources in the dry season (Kyoochul Ha 2013, p.38). However, there are areas with evidence of long-term decline in groundwater level in Cambodia that is not environmentally sustainable. Aquifers are recharged by rain at a very low rate: it was estimated that the rates are on average 1.5% of annual rainfall, between 10 and 70 millimeters per year. It is also difficult to successfully drill wells, due to complicated geology (Vouillamoz et al., 2016, p. 199-201).

1.3.3 Rainwater harvesting

Cambodian rainfall yield is high enough to collect water for both domestic water supply and irrigations. JICA in 2002 showed that using rainwater as a water source is a traditional practice and that 87% of the 303 villages in two provinces, Kampong Cham and Kampong Chhnang, of Cambodia used rainwater harvesting. It is common for households to have 2-3 traditional pieng jars with a capacity ranging from 800 and 1,200 litres. However, the government of Cambodia does not consider the use of rainwater as an improved source unless it is stored in a tank of over 3 m3 (World Bank -WSP 2015, service delivery assessment, p.23) and therefore estimates a lower level of access to water supply in rural Cambodia.

About 97% of dwellings in 2016 had hard/permanent roof materials, and about 3% had soft/temporary roof materials. The most common roof material in the country as a whole was galvanized iron/aluminium, which constituted about 52% of the total occupied dwellings, followed by tiles, about 27%. The third most common roof material used was hard/temporary fibrous cement, which accounted for about 10% (CSES 2016, p.9). In many areas where it is difficult to get access to an alternative water supply as salty water, mountainous and arsenic affected areas, rainwater plays important roles in the provision of clean and safe drinking water solutions. The Water and Sanitation Program of the World Bank completed a study in 2011 on the options for safe water access in arsenic affected areas in Cambodia and recommended that an effort be made to focus on rainwater harvesting with year-round storage capacity for a good clean water system; and possibly a secondary focus on piped water system (Andrew, 2011).

The alternative water access strategies that should be explored to ensure sustainable use of groundwater is to focus on increasing rainwater storage at both the household and community levels. There are two parts to increasing rainwater harvesting supply: rehabilitation of existing sources and increasing the number of storage infrastructure. At a minimum, a family of five requires 3,000-5,000 litres of water for drinking and cooking throughout the dry season (AE-WFP 2016, P.24).

2. National Action Plan (NAP) on water supply, sanitation and hygiene 2014-2018

The NAP set targets of 60% improved access for rural areas and 85% of piped access for urban water supply by 2018, and the NAP 2019-2023 is being developed by reflecting the key learning from NAP 2014-18. Universal access targets to be met by 2025 have officially been adopted for rural sectors in the National Strategic Plan for Rural Water Supply, Sanitation and Hygiene (RWSSH) 2014-2025. Recently, the impact of climate change events such as floods and droughts in Cambodia has increased: in early 2016, Cambodia experienced an extreme drought that affected all 25 provinces and cities, or approximately 2.5 million people in total (MRD/UNICEF 2016). This has led to an increased need of water with many crops and animal dying in some affected provinces, and there is a need for adaptation and increased resilience to climate change.

The NAP 2014-2018 and the National Strategic Development Plan set forth the vision of granting “Everyone in rural community sustains access to a safe water supply and sanitation services and lives in a hygienic environment by 2025”. There are five main strategic objectives of the NAP which cover (i) institutional capacity for RWSSH service delivery, (ii) increase financing for the provision of RWSSH services, (iii) promote and increase access to sustainable rural water supply service, (iv) promote and increase access to sustainable rural sanitation services, and (v) promote sustained hygiene behaviour change in relation to rural water supply and sanitation..

The Department of Rural Water Supply (DWRS) of the Ministry of Rural Development (MRD) oversees water supply in rural Cambodia. In particular, DWRS is mandated to support and facilitate development partners involved in rural water supply; development and manage planning and allocate tasks to the sub-national level.

The Provincial Department of Rural Development (PDRD) adapted the NAP to establish its Provincial Action Plan (PAP) to be implemented at the sub-national level by working directly with district administration and commune councils. Common understanding, knowledge and willingness of local actors are key to plan implementation in target areas. The commune and district authorities have been engaged in the planning process and launching the plan for implementation. In particular, the improvement of institutional capacity for the RWSSH national action plan service delivery presented clear expected outcomes and indicators for roles and capacity building of MRD and PDRD in implementation of national action plan from national to community levels.

The NAP calls for local governments, including district administrations and commune councils, to play increasingly active roles in identifying RWSSH priorities, and allocating investment funds towards those priorities. To assist with this process, NAP calls for selection and training of district and commune focal persons who will advocate for and support NAP/PAP at local level. PDRD and provincial working groups help oversee and support the decentralization effort which includes the delegation of governance and budgetary authority to sub-national administrative units.

3. Roof harvesting: Community perception of traditional rainwater harvesting in rural Cambodia

In 2016, RWC conducted a qualitative research titled “roof harvesting- community perception of traditional rainwater harvesting in rural Cambodia” as a case study of Oral district, Kampong Speu province. The researchers met a wide range of stakeholders including the government, NGOs, local authorities and community representatives to understand what they thought about traditional rainwater harvesting, uses and areas of improvement.

The rational of the study is large number of households in rural Cambodia, traditional harvesting practices are highly risky (vector-borne diseases, and inadequate water for drinking and cooking) as they use open-top small jars and other containers to harvest and store water. Little is known about the reasons why the community still not see their risk. They may have either have no choice than drinking like that because of lack of resource to invest in safer technology, because they have other priorities in resource allocation, or because there is an acceptance of the risk associated with the water they drink. The effort made by development partners and government to promote rural water supply, in particular the promotion of rainwater program as included in the national action plan for rural water supply and sanitation, broadly present the key implementation activities and relied on the its development partners.

Therefore the research has explored community perceptions of harvesting and use of rainwater by adopting qualitative approach. The research analysed three main attributes of perception on Affordability, Convenience and Reliability and has defined the key factors needed to improve rainwater harvesting. Community perceptions provides RWC and its partners in development with key findings that could help tailor development of improved rainwater promotion at scale through a joint commitment to seek funding for pilot project addressing the main concerns raise by respondents; development operation guideline, informed choice of rainwater harvesting

option for improved rainwater harvesting promotion in rural Cambodia.

The study by RWC analysed three key attributes of community perception as affordability, convenience and reliability, and the results are shown in the following:

The findings presented in Graph 1 show the respondents’ answers to open questions for indepth interview for 12 households in response to the three key attributes as presented. There were Eight respondents said that they were very satisfied with odour and color (clear and tasty) while two said they can harvest rainwater at home and water is available.

3.1 Affordability

The house condition of households in Kampong Speu province was found to be suitable for installing a rainwater harvesting system, and all local inhabitants owned their houses. The households that had a good economic status and a good house had the facilities to adopt rainwater harvesting. In addition, Kampong Speu province had good rainfall with an average of 1,414 mm per year. Residents could easily afford rainwater harvesting, some houses could afford gutters and down pipes while some households can harvest directly from the roof by using a zinc sheet. The harvesting practices depended on the financial resources and knowledge available to the houseowner. Gutters and pipes were not available in the village or commune centre so inhabitants have to travel around 40km to provincial town or district town in order to buy these.

3.2 Convenience

Most of the respondents were satisfied with the quality of water in all three areas of odour, taste and colour. All of them confirmed they have traditionally harvested and used rainwater since older generations and most of them considered rainwater as a good source because it is pure water that fell from the sky. The research found many respondents prefer using rainwater as it is clear, tasty and has no muddy smell. In addition, they perceived that harvesting and using rainwater would reduce their water expenditure and time collecting or buying, help them maintain good health and overall allow them to feel more at ease. The Department of Rural Water Supply perceived that Cambodians prefer using rainwater to other sources, in particular for drinking, as it was clear and tasty. In particular, the current rainwater harvesting system has potential for upgrading from the traditional to improved systems and contributing to the increased access to improved water supply targets of Cambodia.

3.3 Reliability

Rainwater is most reliable during the rainy season because most people only have small storage capacity, meaning that if there is an extended period between rains then their storage could become empty. The availability of water in each household varied with the types of usage (irrigation, drinking, cooking, etc.); and storage capacity.

During the rainy season, rainwater topped the ranking of all sources in terms of supply. The households that have storage capacity greater than 2,000 litres are able to solely rely on rainwater throughout the rainy season while households with less than 2,000 litres (having one to three jars) still require other sources. Through the visit, it was found that poor households tend to have one jar and in the rainy season they use water from tube well in their village to supplement their rainwater supply.

Government and commune focal points perceived the key factors to promote improved rainwater harvesting and reach the SDG 06 to be capacity building and raising awareness of promoters and communities, financial capacity of pilot projects and harmonization among sectors and grass root communities for program implementation. They are confident they will be able to grant access to water supply to a large number of households in rural Cambodia by promoting improved rainwater harvesting systems. Besides the research findings, there has been a continued effort made by the DRWS on the development of an informed choice on rainwater harvesting for households system in Cambodia in collaboration with RWC and the sub-group dedicated to improving drinking water quality.

4. Rainwater harvesting formalization in rural Cambodia by RainWater Cambodia

RainWater Cambodia has designed and implemented risk-managed rainwater harvesting (RWH) systems since 2004, which were designed to capture the large rainfall in Cambodia and store enough water to last through the dry season. The risk management approach prevents contamination during storage and ensures that water stays safe to drink. RWC has provided RWH systems for households, schools and health centres and since 2004, over 2800 household systems and over 290 institutional systems have been installed throughout Cambodia. Beneficiaries in rural Cambodia manage the systems themselves, ensuring functionality and capability to supply water for drinking and cooking without the need for other treatment facilities, as it is drinkable. The rainwater harvesting delivery method implemented by RWC is outlined below.

4.1 Assessment and identification of beneficiaries

The situation of target areas was assessed to determine the level of access to improved water supply in reference to the technical aspects: number of water infrastructures, quality of supply, quality of water, and the distance and timing to access the water sources. Additionally, the social and environmental aspects have focused on the vulnerable, poor and arsenic-affected areas as well. The assessment has defined the current situation and proposed alternative solutions to improve the situation. Importantly, the assessment findings will offer information in regard to the amount of water required for consumption and hence the size of tanks.

4.1.1 Local institution

The improvement of water supply in rural Cambodian schools was assessed by investigating schools’ current water assets, water use of students and teachers, the condition of buildings and roofs, the number of students and teachers, and the schools with available water budget or ability to install a rainwater harvesting system. This assessment was then summarized in a report, which is issued to the schools and used as the basis for rainwater design.

4.1.2 Households

For the selection of beneficiaries, a number of factors including economic status, vulnerability and access to drinking water were examined. In Cambodia, data for identifying poor households has been established and adopted in many development programs. RWC also uses the poor households list in the selection process.

4.2 Technical training provided by the local private sector

RWC’s mission statement discusses the development and support of the local private sector in project implementation. The project financially subsidized up to 70% of the total cost for each system for the interested community representatives who invested in rainwater harvesting systems constructed by local entrepreneurs trained by RWC.

Indeed, this is an important part of RWC’s work to contribute to the sustainable development of Cambodia and as such, comprehensive training program were offered to interested entrepreneurs during projects. RWC trainings are designed to cover all the relevant aspects of building rainwater harvesting including theory sessions on the products and materials used, clearly explaining why poor-quality cheap materials result in low-quality products and safety considerations. RWC technicians then build demonstration products before the trainees are encouraged to demonstrate their abilities.

Further to technical training, entrepreneurs are also given some basic business training, including the benefits of marketing and advertising, efficiency of operations and some basic finance and accounting skills. To further ensure that construction is of good quality, construction validation visits are made during RWC projects where the construction site is visited at 80% and 100% of completion whereupon subsidies are paid to the contractor if the work is of acceptable quality. This comprehensive support of the local private sector is to ensure the beneficiaries are provided with good-quality products and to also instill in the entrepreneurs an understanding and appreciation of quality work.

4.3 Supporting local authorities on project implementation

RWC is committed to supporting the Royal Government of Cambodia’s decentralization and de-concentration processes. Commune councils and local authorities selected as focal points participated in project implementation and were trained by the project team. Additionally, the support and involvement of provincial, district and communal governments in development projects is vital to the sustainable development of Cambodia, and RWC involves many levels of government in all of its projects. The Provincial Department of Rural Development (PDRD) is especially actively involved and played a vital in providing support and technical advice to RWC during projects.

4.4 Technical options and construction

The risk management model focuses on the harvesting, storage and distribution parts. All parts consist of a collection system (roof, gutter, first flush system and PVC pipes), a storage system (tank) and a distribution system (PVC piping and taps).

Screens are installed at critical points to prevent animals, mosquitoes, leaves and dirt from entering the tank. A cleaning outlet at the base of the tank enables periodic flushing of the tank to clear any debris which may settle on the tank floor.

The first flush system is designed to divert a calculated volume of water from entering the main tank, and this ensures that the first bit of water that has collected dirt and debris from the roof and gutters is diverted to a secondary tank that is either manually or automatically emptied.

The Royal University of Phnom Penh, Penh Socheat 2009 conducted the study in Kampong Speu on rainwater harvesting with risk-managed system under RainWater Cambodia project, which showed that E. coli and other coliform were present in the water of one recipient household which removed the first flush system, and the water required further treatment options in order to be safe for drinking. The other 15 households which kept the first flush system installed were found to have good quality water which was directly drinkable (Penh Socheat 2009). This is a significant finding of how important it is to have a risk-managed model.

4.5 Institutional system

For larger systems, RWC’s skilled technicians and engineers who have many years of experience oversee the construction, which is for the large ferro-cement tanks and other products. The cost of the system ranges from $US 1,700 to $US 4,000 depending on the size and location. The size of the tank starts from 14,000 litre and goes up to 35,000 litre. Large ferro-cement tanks are

Figure 2 – Risk managed rainwater harvesting tank technically challenging to construct as quality materials must be used and care must be taken at every step. RWC also provides certified technical training to local masons and entrepreneurs who can then construct the tanks.

4.5.1 Domestic system

Domestic rainwater harvesting systems promoted by RWC include two different types of 3,000-litre tanks: the concrete ring tank and the jumbo jar. It is important to remember that other domestic rainwater harvesting technologies are available in different sizes and technical standards. Moreover, it should be emphasized that the tank is just one part of a complete domestic rainwater harvesting system and that each part plays a very important role. Within this specification of the system, the cost ranges from $US 160 for a jumbo jar to $US 250 for a concrete ring tank.

4.6 Operation and maintenance training

An important part of any rainwater harvesting project is operation and maintenance training to ensure sustainability of the system. Typically, an orientation of the different parts is given including demonstrations of how each part works, how to empty the first flush system, turn the valves on and off, clear the screens, and clean and flush the tank, and the importance of keeping the gutter free from leaves is also explained. The beneficiaries are also provided with a number of spare parts and instructions on how to repair parts of the system.

Also provided with the training is a clear easy-to-follow manual which can be kept in the school, and posters highlighting the system are displayed in staff rooms. The manual contains contact numbers of RainWater Cambodia, and if a local mason was involved then his contact details are also provided to the school.

4.7 Project benefits

RWC has received positive feedbacks from all project stakeholders in regard to the project approach and the achieved outputs, and RWC is well recognised in Cambodia as being very successful in the formalization of rainwater harvesting. Besides the number of water facilities built throughout rural Cambodia, the main outcomes of the program have been defined as impact for health, social and environmental aspect also. Table 1 presents the number of rainwater harvesting systems formalized in Cambodia by RWC since 2004.

4.7.1 Health benefits

Health benefits were observed through the feedbacks from households with rainwater harvesting system as the number and frequency of vector-borne diseases have been decreased. Peter McInnis conducted a pilot study in 2008 of rainwater harvesting programs in Cambodia and the results showed that rainwater was considered to be of very high quality by both recipients and non-recipients and was thus used extensively. Both categories of participants still collected large quantities of water and although the majority of recipient households still had most of their tank water remaining, several used it all for non-essential purposes (PETER Mclnnis 2008).

4.7.2 Environmental benefit

This project has demonstrated the

appropriateness of zero energy use for a water treatment before drinking. In 2016, RWC won the national Energy Globe Award – Austria 2016 in recognition of its rainwater harvesting formulization project in rural Cambodia, which contributed to promoting environmental friendly practices and health. The households with rainwater harvesting system built were able to save time and fuel costs by not collecting water from the community pond or other sources.

RWC implemented community-based climate change adaptation in which rainwater harvesting system is one available innovation for the vulnerable households and communities. The vulnerability reduction assessment (VRA) based on the model of UNDP was conducted before starting and after completion of projects to measure the level of project success in particular with respect to climate change risks like drought. The post-project VRA result is compared in Table 2, which shows a significant reduction in the risk of further climate change impact.

5.1.1 Social Benefit

This project has significantly supported the decentralization efforts of local authorities through the establishment of an operation and management committee and implementation of training on social accountability and demand for good governance. Project sustainability has been a critical focus for RWC within this project. The knowledge and resources were mobilized and absorbed by local communities, which ensured that the local private sector, masons and labourers have enough capacity to construct the rainwater harvesting system; and can be selected as a counterpart in construction for other donors and partners in Cambodia.

The project has strongly reinforced the capacity of its partners, such as government technical departments, local authorities and the private sector in regard to relevant design and construction processes for the implemented technologies.

6. Sustainability assessment of rainwater harvesting system

RWC conducted the sustainability assessment of household rainwater harvesting systems in four provinces of Kandal, Kampot, Kampong Speu and Kampong Chhnang in 2016. Ten rainwater harvesting systems installed between 2005 and 2016 were selected in each province. Two technical options were installed in rural communities. These were jumbo jars and concrete ring tanks with a volume of 3,000 to 5,000 litres per unit.

Three main objectives of this study were (1) to understand the current condition of rainwater harvesting systems and associated practices for households with systems implemented by RainWater Cambodia, (2) to determine the level of functionality and sustainability of those systems, and (3) to identify defects or constraints to support future decisions on implementation. The criteria for assessing sustainability were adopted from the UNDP-World Bank Water and Sanitation Program by Sara, J. and Katz (1997) which were: physical condition, operation and maintenance, budget, user satisfaction and willingness to sustain the system. The sub-indicators were scored and rated in a 10-point scale, summed up then divided by the number of total sub indicators. Then, the study identified strengths, defects and constraints from scores obtained for future improvement and implementation for sustainability.

At the time of assessment, 36 rainwater harvesting systems (90%) were still functioning while the other 4 systems (10%) had failed in operation due to broken concrete foundation and crack on storage wall. However, the problems can be fixed by local masons. From rainwater practice findings, the majority of respondents used ‘rainwater’ as their main supply source of water in the rainy seasons but a much lower use of the source in dry seasons due to high demand, lack of rainfall and failure to separate stored rainwater for consumption.

As for the quality of rainwater stored in tanks as drinking water, 18 systems (50%) reported that they did not store other supply sources in storage tanks while the other 18 systems (50%) said they put alternative water sources into the storage tanks. Tested with the Cambodian Drinking Water Quality Standards (2015), those systems with various sources of water storage failed to meet the standards in each parameter.

Table 3 shows the results from the RWH systems assessment. It is classified as being ‘potentially sustainable’ with a score of 6.9 out of 10.0 points. The physical conditions of the concrete foundation, concrete of storage tank and water catchment roof were all good. On the maintenance works, the respondents said they can do some repair works or replace spare parts if there was any minor error such as pipe leakage or broken pipes. For operation and maintenance budget, 78% of respondents had the financial capability if there was a need for minor repair works, despite the fact that more than 50% of respondents were identified either as poor (Poor I) or the poorest (Poor II) according to the national poverty identification system.

All users were satisfied with rainwater in terms of color, odor and taste, but the small storage capacity could not give the users enough water to last throughout the dry season. Many responses were positive on improved health (associated with waterborne diseases) with fewer cases of diarrhea or typhoid in the last six months. Other benefits noted by users of the rainwater harvesting systems were reduced time in obtaining water and saving money.

7. Lessons learnt and the way forward

This article presents the key opinions on how to successfully supply water in Cambodia, which is focused on increasing the effectivness of the national action plan implementation and institutional capacity building program for all relevant stakeholders from national level to grass root communities and promoting improved rainwater harvesting. DRWS and commune focal points perceived that the key factors to promote improved rainwater harvesting could help meet the sustainable development goal on clean water, by focusing on capacity building and raising awareness for promoters and communities, financial capacity of pilot projects and harmonization among WASH sector and grass root communities for program implementation.

In addition, the following key recommendations are more focused on improving rainwater harvesting formalization in rural Cambodia. Experts and studies reported that the effectiveness of rainwater harvesting systems can be improved by increasing the capacity of existing storage tanks and installing new facilities. In particular, based on the sustainability assessment findings, RWC proposes the key recommendations in Table 4 on its rainwater haresting formalization in rural Cambodia to contribute to the affordable and clean drinking water for Cambodia as the following:

Table 4 – Key recommendations

8. Conclusion

The NAP 2014-2018 clearly presented the flow of work and targets to achieve by 2018, and the second NAP 2019-2023 framework is under deveolopment. In the first mandate of the plan, the mid-term review has been conducted by MRD and its partners to define key learnings, basic strategy and planning to achieve expected outcomes.

Rainwater harvesting formalization is feasible and widely adaptod by the communities, and many Cambodians prefer rainwater as their main source for drinking and cooking. However, the collection method needs to incorporate a risk management model. RWC has introduced the new risk management model as presented in the above section in an attempt to mitigate all risks and make the system easy to construct for local people. Some studies found that the rainwater harvesting program brought health, environmental and social benefits. Additionally, this technical option can be applied to the areas where alternative water sources are unavailable. From the business perspective, rainwater harvesting is not commercially viable yet as people need subsidies from donors and governments. Moreover, the system is only able to supply enough water for drinking and cooking.

The improvement of existing traditional rainwater harvesting has focused on mitigating the risk from contamination and ensuring enough water is supplied for drinking and cooking year-round by meeting the definition of access to improved water supply: (i) safe storage, (ii) storage capacity of at least 3,000 litres, and (iii) access to water through a tap. The World Food Program is carrying out a strategy to ensure access to water by promoting rainwater harvesting storage (AE-WFP 2016, p.2). There are two parts to increasing rainwater supply: rehabilitation/improvement of existing sources and installation of new facilities to increase the number of water jars or increase storage capacity up to 3,000-5,000 litres to supply water all year round. To sustain the rainwater harvesting formalization, RWC should improve its rainwater harvesting program by specifically focusing on the five criteria of sustainability; and should capture the strength as found in sustainability assessment and improve the systems from potential sustainability to sustainability. In addition, the government of Camdodia represents by Ministry of Rural Development should put more investment in mobilization of rainwater harvesting by development of the operational guideline, demonstrate of model project and scale up. The increased effort in implementation and focused on improve traditional rainwate rharvesting to an improved risk managed system either National Action Plan (NAP) or Provicial Action Plan (PAP) on water, supply, sanitation and hygiene are keys to in crease access to improve water supply.

In conclusion, rainwater harvesting formalization in rural Cambodia is an alternative and sustainable water supply solution for everyone in rural Cambodia as it is affordable, reliable and convinient.

References

1. AE-WFP 2016, Water Infrastructure Study: Rapid Assessment of Existing Groundwater Studies and Groundwater Use in Cambodia.

2. ANDREW SHANTZ & WILLIAM DANIELL 2011,Water and Sanitation Program: A Study of option for safe water access in arsenic affected community in Cambodia

3. CSES 2016, Cambodian Socio Economic Survey, P.9, National Institute of Statistic, The Kingdom of Cambodia.

4. FAO, UNICEF, WFP – 2016, Household Resilience in Cambodia, A Review of Livelihoods, Food Security and Health, Part 12015/2016 EI Nino Situation Analysis.

5. JICA 2002, P.8-4 The Study on Groundwater Development in Central Cambodia, Final Report.

6. JMP update report, WHO-UNICEF 2015, P.4, Progress on sanitation and drinking water

7. Kevin Watkins, 2006, P.34, Human Development Report, UNDP

8. Kyoochul Ha et all 2013, “Current Status and Issues of Groundwater in the Mekong River Basin”, KIGAM) CCOP Technical Secretariat UNESCO Bangkok Office.

9. Kea Pheng 2016, roof harvesting – community perception of traditional rainwater harvesting in rural Cambodia. A final thesis for executive master in development policies and practice, at the Graduate Institute of International and Development Studies in Geneva, Switzerland.

10. National Strategic Development Plan 2011-2018, The Royal Government of Cambodia

11. National Strategy for Rural Water Supply, Sanitation and Hygiene, 2011-2025

12. National Action Plan 2014-2018, Rural Water Supply, Sanitation and Hygiene in Cambodia.

13. PETER Mclnnis 2008: Pilot study for evaluation of the impact of rainwater collection system for villagers in rural Cambodia.

14. Penh Socheat 2009, the study on rainwater harvesting formalization in Kampong Speu, Cambodia: A final thesis for Bachelor Degree at The Royal University of Phnom Penh, Cambodia.

15. RWC 2013, Climate Change Adaptation Project: Post-Vulnerability Reduction Assessment in Kampot Province.

16. SNV-MRD 2015, P.24, Rural Water Supply Technical Design Guideline and Construction Supervision Manual

17. Sara, J. and Katz, T. 1997. Making Rural Water Supply Sustainable: Report on the Impact of Project Rules. Retrieved from http://www.wsp.org/UserFiles/file/global_ruralreport.pdf. Accessed date: 10/2014.

18. SEVEA 2017, Access to drinking water in rural Cambodia. Current situation and development potential analysis report.

19. WSP 2015, p.23, service delivery assessment, Water and Sanitation Program – World Bank.

20. World Bank Group 2017, Sustainability Assessment of Rural Water Service Delivery Models, finding from a multi-countries reviews.

21. Vouillamoz, J. M., Valois, R., Lun, S., Caron, D., & Arnout, L. (2016). Can groundwater secure drinking- water supply and supplementary irrigation in new settlements of North-West Cambodia? Hydrogeology Journal, 24, No. 1 (February): 195-209.

22. WHO-Guideline for drinking water quality, 2008, Third Edition, p120e

23. WHO 2005, P.29, water safety plan, drinking water quality guideline

24. (MRD/UNICEF, 2006, MRD WASH drought response, Drought Condition Update, 06 June 2016.